The tariffs that were due to go into effect against Mexico and Canada today have been put on hold for at least a month.

The deferral was not a surprise to me. I have long seen the tariffs as an exercise in leverage rather than a policy valued in its own right, and the White House statement accompanying the executive order was explicit about using our “economic position as a tool” to extract concessions from trading partners. Even the manner of implementation telegraphed the intent. The executive order authorizing the tariffs was signed on a Saturday, while markets were closed, and allowed for enough time to observe market reaction on Monday before going into effect.

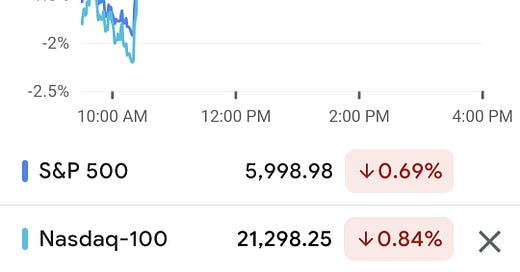

Market movements under such conditions are hard to interpret because they incorporate the possibility that some sort of negotiated settlement could emerge, and the awareness that the sharper the decline the more likely the reversal. As it happens, the decline in market indexes was relatively muted and largely reversed once a deal with Mexico was announced:

The tactics being pursued here were described quite clearly by Thomas Schelling in his classic book The Strategy of Conflict:

How can one commit himself in advance to an act that he would in fact prefer not to carry out in the event, in order that his commitment may deter the other party? One can of course bluff, to persuade the other falsely that the costs or damages to the threatener would be minor or negative. More interesting, the one making the threat may pretend that he himself believes his own costs to be small, and therefore would mistakenly go ahead and fulfill the threat. Or perhaps he can pretend a revenge motivation so strong as to overcome the prospect of self-damage; but this option is probably most readily available to the truly vengeful.

In order to make threats credible, it is necessary to maintain ambiguity about one’s true motives, and occasionally inflict damage on oneself. In fact, while the proposed tariffs against Mexico and Canada were deferred, those against China went into effect at midnight and were met with immediate retaliation in the form of levies, export restrictions and sanctions.

I argued in an earlier post that the exercise of power in this manner eventually depletes it, through changes over time in trading patterns and global alliances. But there is also a more immediate cost to belligerence. The schoolyard bully may get your lunch money from time to time but won’t be invited to join your study group or attend your birthday party. Nobody likes to be pushed around. People will use whatever limited power they have at their disposal to find a way to retaliate, and when they do so in large numbers the effects can be quite significant.

Amid all the threats and bluster, Canadians are canceling planned vacations to US destinations and boycotting American products. No matter what kind of negotiated settlements emerge over the coming months, such changes in expenditure patterns will not be easily reversed.

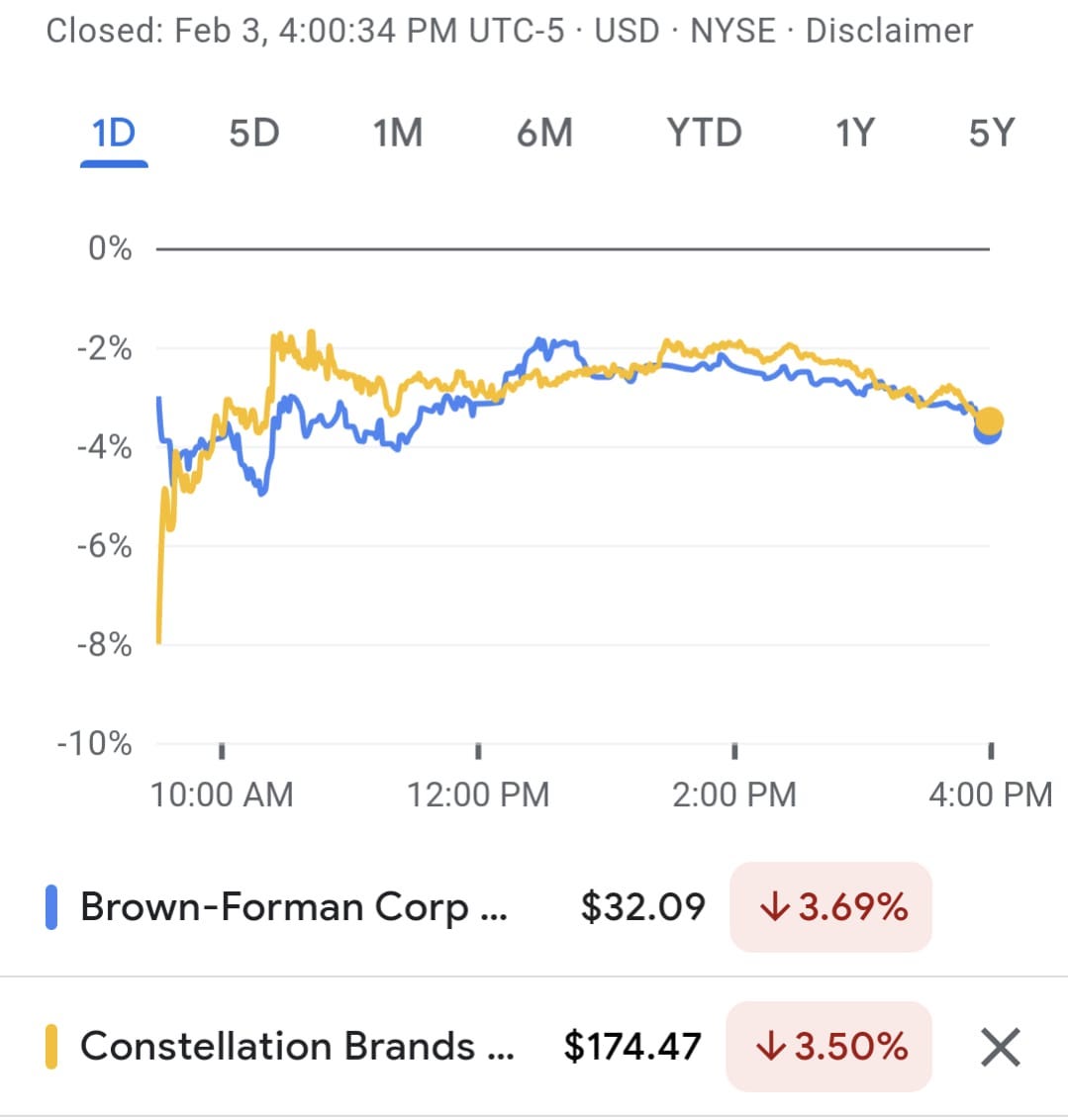

Consider, for instance, two companies—the Brown-Forman Corporation and Constellation Brands. The former’s portfolio includes one of the most globally recognized American products: Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Whiskey. And the latter is the sole importer of Corona, Modelo, and Pacifico beers, all manufactured in Mexico. These two stocks fell much more than the market as a whole yesterday:

While Constellation recovered sharply in the wake of the Mexico deal, it was still down 3.5 percent for the day. Brown-Forman was down even further. If I were to guess (and this is not trading advice by any means) I would say that the importer has better prospects for recovery than the exporter at this point. No amount of negotiation can restore brand loyalty once it is lost.

The administration’s approach to trade might cost a few iconic brands some export revenue, but its approach to foreign aid is going to cause much greater harm:

The programs that have frozen or folded over the past six days supported frontline care for infectious disease, providing treatments and preventive measures that help avert millions of deaths from AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and other diseases. They also presented a compassionate, generous image of the United States in countries where China has increasingly competed for influence.

The consequences of this for the affected populations will be immediate and dire. The bipartisan PEPFAR program alone is estimated to have saved 25 million lives. But the abrupt cessation of health initiatives and clinical trials worldwide will also harm American interests, as is recognized by some of the president’s own supporters. We can survive the erosion of value in some iconic product brands. But it will be much harder to adjust to a loss in value of the American brand writ large.