We are about a month away from a new administration in the US and there’s a distinct possibility that across-the-board tariffs will be imposed against our three largest trading partners.

Economics offers (at least) two different ways to think about the logic and consequences of this. One is through the lens of open economy macroeconomics, with its focus on capital flows and the exchange rate. The other is from the perspective of games with incomplete information, which highlights the credibility of threats and strategic responses to uncertainty. Both approaches are valuable here.

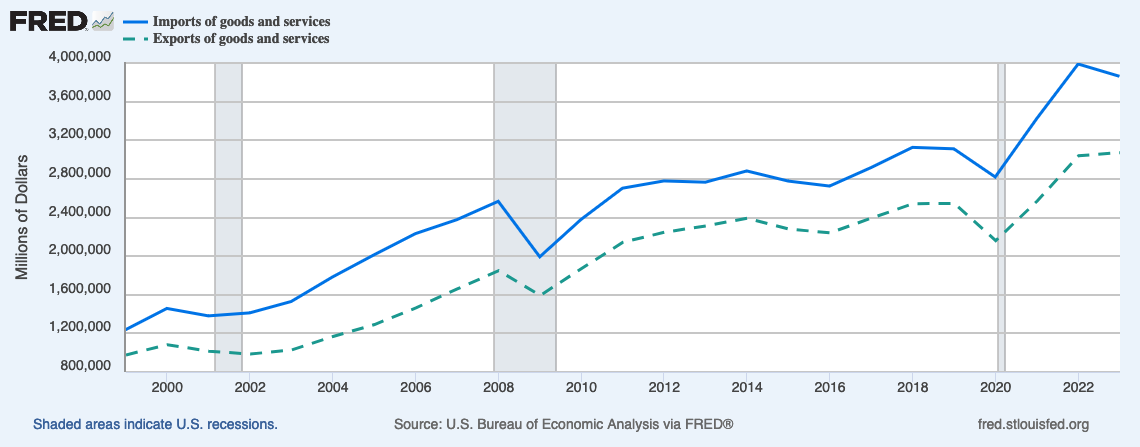

First, some background. We buy more goods and services from the rest of the world than they buy from us. This trade deficit has persisted for three decades, even as exports and imports have both grown:

Our annual trade deficit in 2023 was about 800 billion dollars, down from almost a trillion dollars in 2022. Approximately half of this deficit arises from trade with the three countries being targeted for tariffs, and about a third is attributable to trade with China alone.

These countries are therefore very vulnerable to changes in US trade policy—a significant and sudden imposition of tariffs would result in a collapse of demand for their products, with immediate and catastrophic consequences for output and employment.

Of course, the imposition of tariffs would have major consequences for our own economy also, even in the absence of retaliation by our trading partners. These effects have been examined in depth by Paul Krugman in a recent post.1

Krugman’s argument may be summarized as follows. Our balance of payments—the ledger that records all transactions with the rest of the world—must balance. If we buy more from others than they buy from us, then they accumulate claims against our future production. They can do this by buying assets such as stocks, bonds, and real estate that show up in the balance of payments as capital inflows. Trade deficits and net capital inflows are thus two sides of the same coin: if tariffs lower the former, then they must also lower the latter.2

Krugman argues that this will happen through an appreciation of our currency, which will make our assets more expensive for foreign investors and choke off demand. Furthermore, a stronger dollar will also make our goods and services more expensive to foreign buyers, and thus blunt any effect of tariffs on the trade balance. The result will be a contraction of global trade and international capital movements.

This analysis is logically sound, of course. But it might be missing something important about the goals and effects of the threatened tariffs.

To see why, recall that the targeted countries have more to lose from a trade war than we do, at least in the short run. They are desperate to avoid this. The Canadian Prime Minister has already visited Mar-a-Lago, and his administration is drawing up plans to increase border control and drug interdiction. Similar steps are being undertaken in Mexico. Meanwhile, China appears willing to buy more of our exports, which would reduce our trade deficit by increasing rather than decreasing the volume of global trade.3

These responses by our major trading partners suggest that the threat is not being seen as a bluff, despite the fact that tariffs are likely to harm all parties involved. The reasons for this were laid out very clearly by Thomas Schelling in his 1960 classic The Strategy of Conflict:

How can one commit himself in advance to an act that he would in fact prefer not to carry out in the event, in order that his commitment may deter the other party? One can of course bluff, to persuade the other falsely that the costs or damages to the threatener would be minor or negative. More interesting, the one making the threat may pretend that he himself believes his own costs to be small, and therefore would mistakenly go ahead and fulfill the threat. Or perhaps he can pretend a revenge motivation so strong as to overcome the prospect of self-damage; but this option is probably most readily available to the truly vengeful.

This idea has been developed in a series of influential papers that explore the effects of uncertainty about the motives and rationality of strategic opponents.4 In the case of the tariff threat, it appears that Donald Trump has managed to convince other world leaders that he considers the risks to our own economy to be negligible, and that he is endowed with truly vengeful motives. This makes the threat credible, and elicits the kinds of reactions we are seeing.

It is possible, of course, that the president-elect may overplay his hand, implement the tariffs despite concessions by trading partners, and invite retaliation. In this case the scenario spelled out by Krugman (or worse) will come to pass. Prediction markets see this outcome as quite unlikely at the moment, but since erratic behavior is precicely what makes threats of this kind credible, things could change very quickly and without warning. It will take some time for the clouds of uncertainty to lift.

I’m grateful to

for bringing the Krugman article to my attention through his excellent weekly roundup of interesting content online.As Krugman explains, one also needs to take account of other income flows such as remittances by migrant workers, foreign aid, investment income from assets accumulated in previous years, and the accumulation of dollar balances by foreign institutions and residents. Real estate purchases can be seen as acquisitions of prior production or as claims on future residential services; either way they appear as capital inflows. Artwork and collectibles may be viewed in similar ways.

Net capital inflows would still decline, as Chinese residents buy more goods but fewer assets.

Two books that had an enormous influence on me as a graduate student were Schelling’s Strategy of Conflict and John Maynard Smith’s Evolution and the Theory of Games; the combined effect of these influences can be seen in papers on social norms, interdependent preferences, and reputation.

Very helpful piece Rajiv. Many thanks for sharing it.