White smoke was seen rising from a chimney at the Sistine Chapel at around 6:07pm local time yesterday, announcing the election of a new pope. This was revealed to be Robert Francis Prevost—now Pope Leo XIV—at about 7:13pm.

For about an hour, while the world’s eyes were fixed on a balcony in St. Peter’s Square, millions were being won and lost on prediction markets. A close look at price movements during this period of heightened anticipation and frenzied speculation reveals something interesting and quite general about information aggregation and excess volatility.

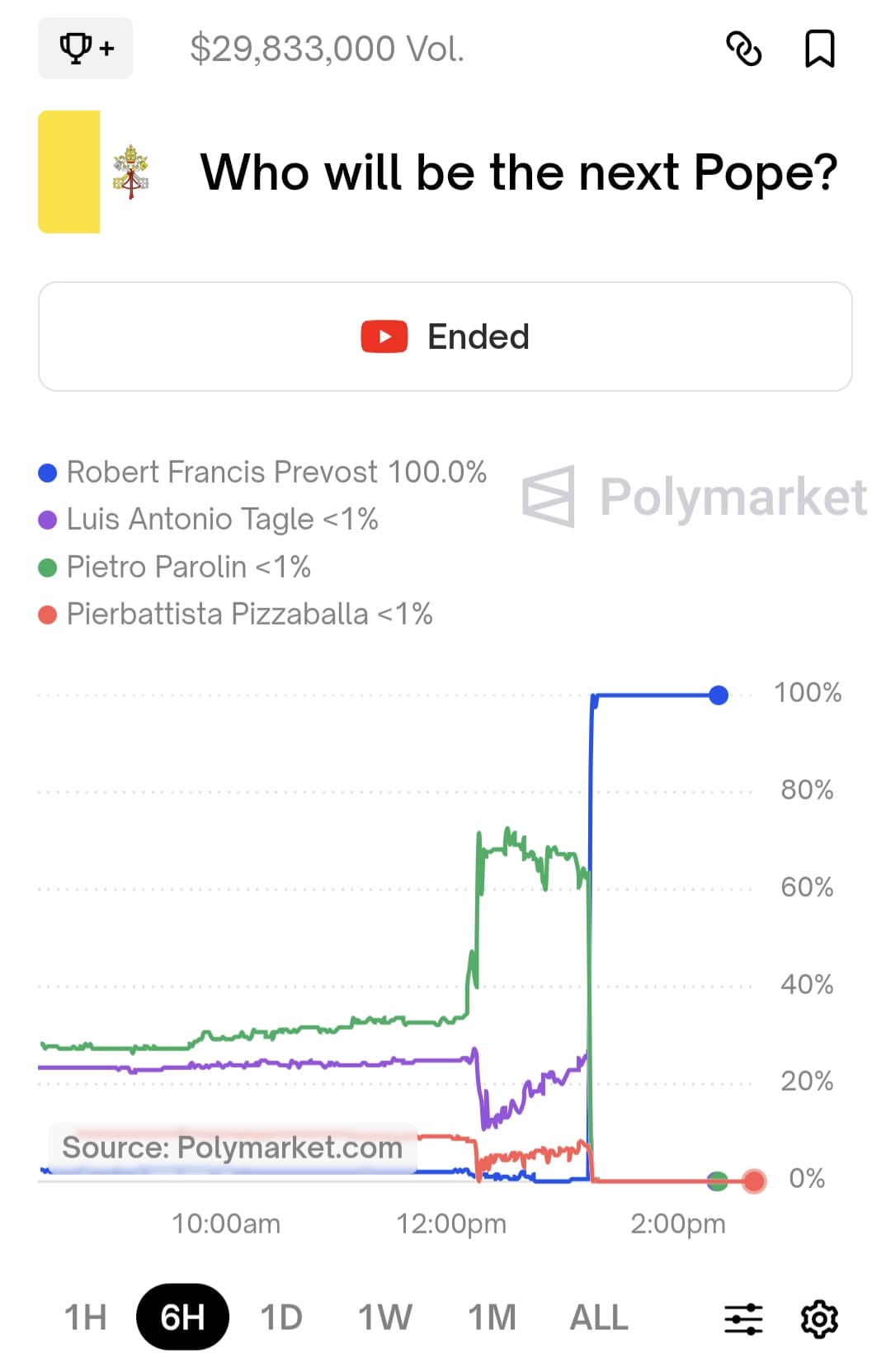

Over the past couple of weeks, more than forty million dollars were wagered on the outcome of the papal conclave. Two candidates—Pietro Parolin and Luis Antonio Tagle—led the field throughout. On Polymarket, just prior to the emergence of white smoke, their implied probabilities of being the next pope were about one-third and one-fourth respectively. The next two candidates—Pierbattista Pizzaballa and Matteo Zuppi—were each given a nine percent chance. Robert Prevost stood far back in ninth place, with a two percent probability of emerging victorious.1

What happened in response to the white smoke was startling. The price of the Parolin contract doubled within minutes, as the other prices slid. It remained above sixty percent for the rest of the hour, before collapsing to zero once the identity of the new pope was publicly revealed:

What could explain these price movements? We can probably rule out information leakage from inside the Chapel, since the price of the Prevost contract actually fell over this period. There was some information content in the timing of the announcement—traders might have interpreted a relatively quick decision as being good news for the early favorite. But the scale of the price increase, as well as the sharp initial decline in the price of the Tagle contract, suggests to me that the explanation lies elsewhere.

Here’s what I think happened. Although it’s clear in hindsight that there was no leakage of inside information, this was not known to traders in real time. They saw the price rising, and tried to interpret this. They knew that the identity of the new pope was known to those who had participated in or witnessed the vote, and the possibility that this information had made its way outside the Chapel walls could not be ruled out.

That is, while no trader knew the identity of the new pope, they suspected that some other traders knew. And by treating the price movements themselves as informative, traders acted in ways that amplified these movements. This confirmed their suspicions, reinforced their actions, and quickly drove prices to levels completely out of step with the information available. In fact, aside from the timing of the announcement, there was no information available at all.

This episode reveals something quite general about financial markets. It shows that momentum trading can be profitable under certain conditions, but also that too much of it can destabilize markets.

When the papal conclave began, it was still May 6 in New York, which happened to be the fifteenth anniversary of the astonishing flash crash of 2010. In writing about this event at the time, I distinguished between trading strategies that are information augmenting, and those that are information extracting. The former stabilize markets, but make price movements informative and hence information extraction profitable. But as the latter strategies proliferate, volatility rises, investments in information become more lucrative, and stability is eventually restored. This periodic regime switching gives rise to clustered volatility.

Many observers claimed victory and vindication for prediction markets after the presidential election last November, but one can’t make judgements about the forecasting accuracy of a mechanism based on the outcome of a single event. The election of a president is one data point, the election of a pope is another. For the latter event, the predictive accuracy of markets could hardly have been worse. But on the bright side, this failure revealed with unusual transparency something about the deep structure and functioning of financial markets in general.

Odds on Kalshi were similar. This is not a coincidence—large differences across markets in prices for the same contract cannot persist for long because they give rise to an opportunity for arbitrage. Traders can buy the contract where it is cheaper, sell it (betting that the referenced event will not occur) where it is more expensive, and make a profit regardless of the outcome. Such trades move prices on both markets in ways that bring them into closer alignment.

For those interested in the history of papal betting markets, they've actually been around for hundreds of years, since around the 15th century. Here's a great podcast on the subject: https://open.spotify.com/episode/3tGa9ZMxctqeEwxBa4B3OE?si=yFnLAUH0Q-mLvjKNrclXKQ&nd=1&dlsi=3dcb85af76524b42