The Summer of 1967

A couple of days ago, a panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that federal control of the California National Guard could continue over the objections of the state’s governor. The decision was unanimous, and opens the door to deployment elsewhere. It is quite likely that over the course of this summer and beyond, we will see considerable contact between protestors and soldiers (including some on active duty) in urban environments with which the latter are relatively unfamiliar. This can lead to catastrophic errors of judgment—fireworks can be mistaken for gunshots, for example, and friendly fire can be thought to be hostile.

Such mistakes are especially likely to happen if the risk of sniper fire is real. The entry of the United Stated into direct military conflict with Iran leaves about 40,000 troops across the Middle East vulnerable to possible retaliation, and one can’t rule out the possibility that soldiers on American streets may also face heightened risks.

In thinking about how the confluence of these two factors—the court ruling and the military strike—might cause events over this summer to unfold, it’s worth thinking about prior periods during which troops confronted civilians across American cities. The summer of 1967 was one such episode. The most intense contact occurred in Newark and Detroit, with about fifty civilians killed in one fateful week. I have appended below an extract from Chapter 8 of my book with Dan O’Flaherty, which looked at the events of that summer in the context of preemptive violence more generally.

One of the points that Dan and I made in our book was this—homicide is unique among (potential) crimes in having a preemptive motive, and this can give rise to very high rates of killing when people are afraid.1 You would not commit burglary or fraud because you fear that such crimes might be committed against you, but people do sometimes take a life for no reason other than to save their own. As Grace Doyle said upon her arrest for killing her husband in 1899: “If I had not put an end to him this morning he would have killed me tomorrow.” Or as Thomas Schelling put it in his classic book, “self-defense is ambiguous, when one is only trying to preclude being shot in self-defense.”

This means that fearsomeness and fearfulness are two sides of the same coin. People who instill fear in others ought to be afraid of preemptive violence, just as people who are afraid are potentially dangerous. This logic applies to all kinds of situations—people engaged in personal disputes, turf wars in streets and prisons, police-civilian interactions, and counterinsurgency. In fact, the excerpt ends with a quote from a field manual authored by Army General David Petraeus and Marine General James Amos, reflecting US military experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq.

I am hoping, of course, that we hear no echoes of the summer of 1967 (or of Afghanistan and Iraq). But sometimes contemplating a worst case scenario is the best way to avoid it.

The summer of 1967 was a tumultuous one, with prolonged and violent civil disturbances breaking out in scores of American cities.2 The resulting deployment of police and military resources led to the greatest concentration of civilian deaths at the hands of law enforcement officers in recent history. In Newark and Detroit alone, more than fifty civilians were killed in less than a week; the current rate of civilian deaths at the hands of police officers is about three a day in the nation as a whole.

Even as riots were still raging in Detroit, President Johnson established the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders under the leadership of Illinois governor Otto Kerner. Seven months later, the Kerner Commission released a report with the following ominous warning: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”

As part of its mandate, the commission was tasked with uncovering what had happened and why. To address the latter question, the commissioners tabulated grievances voiced by members of the affected communities. At the top of this list—ahead of unemployment, inadequate housing and education, white attitudes, and the administration of justice—was a category called “police practices.”

In fact, the triggering incident in many of the riots examined in the report was some form of police action. In the case of Newark it was the arrest of taxi driver and army veteran John Smith, who was falsely rumored to have been killed in custody. And in Detroit it was the raid on a blind pig (an unlicensed drinking and gambling establishment) during a large party for servicemen.3

In Chapter 4, we observed that a climate of fear amplifies violence by increasing the incentive to kill preemptively. This effect is documented very clearly in the Kerner report. The police and National Guard members tasked with quelling the riots were largely young, inexperienced, and unfamiliar with the local conditions and communities. They were especially fearful of sniper attacks, and this led to indiscriminate firing and multiple fatalities. At around 6 p.m. on July 15, for instance, the following sequence of events occurred in Newark:

National Guardsmen and state troopers were directing mass fire at the Hayes Housing project in response to what they believed were snipers.

On the 10th floor, Eloise Spellman, the mother of several children, fell, a bullet through her neck.

Across the street, a number of persons, standing in an apartment window, were watching the firing directed at the housing project. Suddenly, several troopers whirled and began firing in the general direction of the spectators. Mrs. Hattie Gainer, a grandmother, sank to the floor.

A block away Rebecca Brown’s 2-year-old daughter was standing at the window. Mrs. Brown rushed to drag her to safety. As Mrs. Brown was, momentarily, framed in the window, a bullet spun into her back.

All three women died.4

According to the report, “the amount of sniping attributed to rioters—by law enforcement officials as well as the press—was highly exaggerated.” In particular, “most reported sniping incidents were demonstrated to be gunfire by either police or National Guardsmen… The climate of fear and expectation of violence created by such exaggerated, sometimes totally erroneous, reports demonstrates the serious risks of overreaction and excessive use of force.” According to one police source: “Guardsmen were firing upon police and police were firing back at them.”5

The report offers several reasons for the exaggerated fear of sniper attack:

Several problems contributed to the misconceptions regarding snipers: the lack of communications; the fact that one shot might be reported half a dozen times by half a dozen different persons as it caromed and reverberated a mile or more through the city; the fact that the National Guard troops lacked riot training. They were, said a police official, “young and very scared.”

In contrast with the jumpiness exhibited by the police and National Guard members, one section of Detroit was policed by a group of professional soldiers, one-fifth of them black, under the command of Lieutenant General Throckmorton. The behavior and experience of this group is instructive.

According to Lieutenant General Throckmorton and Colonel Bolling, the city, at this time, was saturated with fear. The National Guardsmen were afraid, the residents were afraid, and the police were afraid… The general and his staff felt that the major task of the troops was to reduce the fear and restore an air of normalcy.

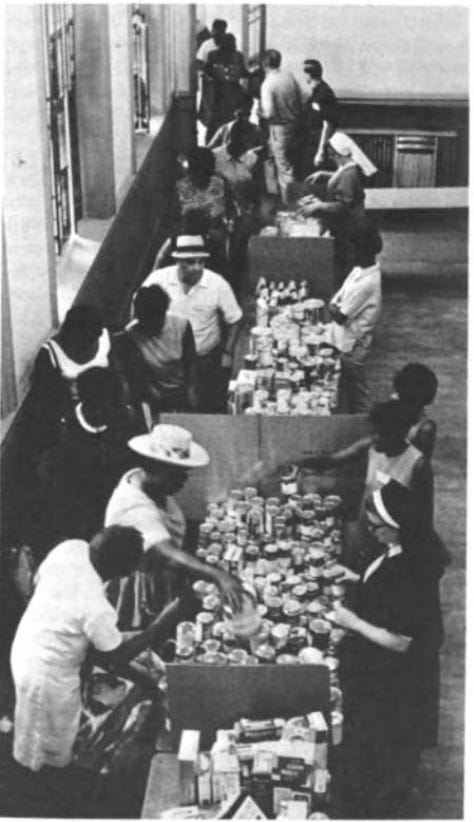

In order to accomplish this, every effort was made to establish contact and rapport between the troops and the residents. Troopers… began helping to clean up the streets, collect garbage, and trace persons who had disappeared in the confusion. Residents in the neighborhoods responded with soup and sandwiches for the troops…

Within hours after the arrival of the paratroops, the area occupied by them was the quietest in the city, bearing out General Throckmorton’s view that the key to quelling a disorder is to saturate an area with “calm, determined, and hardened professional soldiers.” … Troopers had strict orders not to fire unless they could see the specific person at whom they were aiming. Mass fire was forbidden.

During five days in the city, 2,700 Army troops expended only 201 rounds of ammunition, almost all during the first few hours, after which even stricter fire discipline was enforced. (In contrast, New Jersey National Guardsmen and state police expended 3,326 rounds of ammunition in three days in Newark.) Hundreds of reports of sniper fire—most of them false—continued to pour into police headquarters; the Army logged only 10. No paratrooper was injured by a gunshot.6

Not only did Throckmorton’s troops inflict less violence on innocent civilians, but they were also more effective in executing their mission. This phenomenon is familiar to military units involved in occupations of civilian areas. A U.S. Army counterinsurgency manual, for instance, states that “many of the… best weapons for countering an insurgency do not shoot.”7

Excerpt from Chapter 8 of Brendan O'Flaherty and Rajiv Sethi, Shadows of Doubt: Stereotypes, Crime, and the Pursuit of Justice, Harvard University Press, 2019.

.

The qualifier “potential” is necessary here because homicide (the killing of one person by another) is not always a criminal act.

The Kerner Commission report documented 164 civil disorders in 128 cities. Eight of these were deemed major and a further thirty-three serious.

National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (1968, pp. 32, 47).

National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (1968, p. 37).

National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (1968, pp. 180, 37). The quote is from Newark director of police Dominick Spina.

National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (1968, p. 56).

“Any use of force produces many effects, not all of which can be foreseen. The more force applied, the greater the chance of collateral damage and mistakes. Using substantial force also increases the opportunity for insurgent propaganda to portray lethal military activities as brutal. In contrast, using force precisely and discriminately strengthens the rule of law that needs to be established” (United States Army, 2006, p. 1-27).