The Question of Divestment

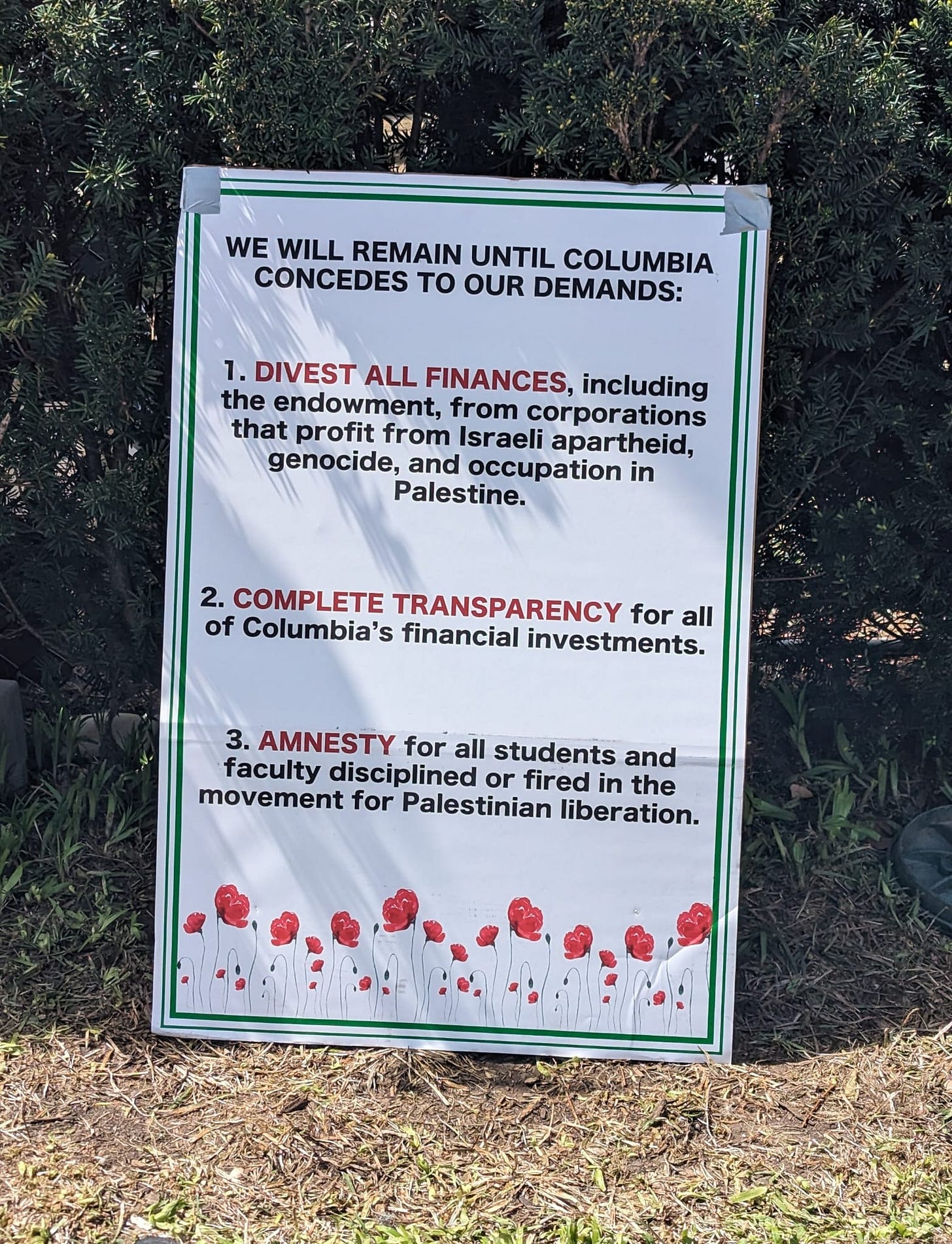

The student protestors who have camped out on Columbia’s West Lawn for the past couple of weeks have repeatedly maintained that “that they will not move until they achieve divestment.” The divestment they seek—as spelled out in a proposal submitted to Columbia’s Advisory Committee on Socially Responsible Investing in December 2023—is from companies judged to be “complicit in Israeli apartheid, illegal occupation, and genocide.” These companies include Alphabet (formerly Google), Amazon, and Microsoft, with a combined market capitalization of more than seven trillion dollars.

The committee rejected the proposal in February, which I imagine was a driving force behind the establishment of the encampment.

I have thought quite a bit about the divestment question over the past few years, especially after being appointed in 2015 to a Presidential Task Force charged with examining “the issues surrounding divestment from fossil fuels.” Our deliberations considered the effects of divestment on the growth of the endowment and on the incentives faced by targeted companies. We argued that the effects would be minor on both counts, reasoning in the latter case as follows:

Divestment involves a transfer of ownership in the secondary market for securities. Since every sale also involves a purchase, the demand for such securities from other individuals and institutions will determine the extent to which divestment will have an impact on the share price of the affected firms. To a first approximation, the anticipated future earnings of firms determine the price of shares in the secondary market. If divestment does not affect earnings, its impact on the share price will be negligible. That is, even a small decline in price relative to anticipated earnings would make the shares attractive to buyers looking for value, and their demand to buy would prevent significant declines. If the affected companies do not experience any change in the cost of raising capital, then the extent of fossil fuel extraction and sale will also be largely unaffected.

As Adam Tooze has pointed out, Columbia’s portfolio has a very small share of direct investment in the specific companies targeted by the protestors. But even if this were not the case, divestment from publicly traded companies would have negligible impacts on their earnings, share prices, and costs of capital. This is especially the case with behemoths such as Alphabet, Amazon, and Microsoft, which have a combined market valuation exceeding a quarter of our annual Gross Domestic Product.

Divestment is therefore a largely symbolic gesture that does not directly create strong incentives for companies to change business practices. This is very different from product boycotts, which can be extremely potent. However, if the publicity surrounding divestment can bring attention to an issue and lead to changes in behavior, it can start to have incentive effects.1

The likelihood that Columbia will agree to the divestment demand is negligible, not because the effects on endowment growth would be significant (they would be barely discernible) but because of the precedent this would set for future actions. Accordingly, unless the students decide that their demand is negotiable after all, there are only two possible resolutions for the current impasse—forcible dismantling of the encampment, or the cancellation of this year’s graduation ceremonies.2

This is the dilemma in which the senior leadership finds itself. It is not an easy situation to navigate, especially when external actors with little love for the university are eager to pounce. It is not inconceivable to me that the transformation of New College in Florida is being viewed as a template for the capture of much larger and more prestigious institutions.

Perhaps in recognition of this, Columbia’s university senate appears to be stepping back from a proposal to censure President Shafik. Meanwhile, my colleagues at Barnard have been moving full steam ahead in the opposite direction. Many of the points they make are legitimate; there have indeed been significant errors of judgment. But the approach taken is adversarial rather than constructive, and thus liable to make a very dire situation substantially worse. I cannot in good conscience join them.

Based on this reasoning, our task force recommendation was to identify and focus divestment efforts on companies that were explicitly undermining climate science. Were I on such a committee today, I would be much more concerned about how sincere dissent within the scientific community could be reliably distinguished from bad faith claims motivated by pecuniary interest.

The option to find an alternative venue probably involves insurmountable logistical challenges at this late stage.