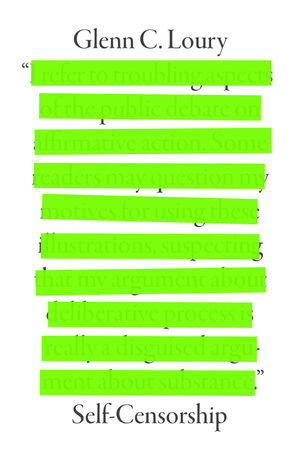

In a recent post I mentioned a forthcoming book by Glenn Loury that contains his classic essay on self-censorship in public discourse, with a new foreword and afterword. I was asked to provide a few words of comment for the jacket, and submitted the following:

Glenn Loury’s brilliant essay on self-censorship is as relevant today as when it was first written. It is published here with a new afterword in which the author argues—through his own poignant example—that the preservation of social esteem by the maintenance of public silence is eventually paid for in the coin of self-respect.

The publisher may choose to edit this, or decide not to use it at all, but I wanted to post it here in its original form as a prelude to a discussion of the “poignant example” mentioned.

The example, as you might have guessed, concerns the war in Gaza.

Loury begins the chapter with the story of an invitation to deliver a lecture on Black-Jewish relations at a synagogue in Florida.1 At the time of the event, this was his state of mind:

The reports of the dead, the grotesque images, and the terrifying accounts of the refugees weighed heavily on me. In the months since Hamas’s brutal attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, the death toll in Gaza had been mounting at a dizzying pace. The US had, in short order, affirmed its support of Israel and was supplying a steady flow of weapons and money, paying only lip service to what I was beginning to view, what I could not help but view, as a humanitarian disaster—not because of dead Hamas militants and their political leadership, who knew what they were signing up for, but due to the dead women, children, and elderly, the dead medics and journalists. The news of dire food shortages in Gaza chilled me, as did images of block after block of bombed out ruins that once housed apartments, schools and businesses.

Israel had a right to respond to Hamas’s attack. Indeed, considering the brutality of the Oct. 7 assault, Israel had a duty and a responsibility to respond. Nevertheless, the killing of thousands upon thousands of noncombatants, while subjecting hundreds of thousands to injury and starvation and destroying the homes of millions, seemed to me an unacceptably high cost to pay for the goal of “eliminating” or “eradicating” Hamas, especially since it was unclear whether and how that goal would ever be accomplished. It also seemed likely that the scope of death and destruction being wrought would inspire more people in the region and abroad to take up arms against Israel than would have been the case had its response been less devastating to the civilian population. What was being done in Gaza, if arguably necessary from Israel’s point of view, nevertheless amounted to a set of horrific deeds with which I was loath to see my own country associated.

These thoughts troubled me. They made me question my longstanding affirmation of Israel’s prerogative to do what it deemed necessary to defend itself, and of my country’s support for the same. When I hinted publicly at my growing doubts about Israel’s actions in Gaza, I received immediate blowback. Friends and strangers alike were emailing me long missives, taking me to task for my historical ignorance, listing figures about “acceptable” civilian-to-combatant death ratios, and reiterating Israel’s embattled regional position. The common refrain that emerged among ardently pro-Israel politicians, media figures, spokesmen and others was this: to suggest Israel was killing too many civilians amounted to a betrayal of the Jewish people. I chafed at this idea. I knew I was not—am not—an antisemite, but it soon became clear to me that giving voice to my misgivings about Israel’s conduct of this war risked having me labelled as one.

Suspecting that the public expression of such thoughts “would be grievously offensive to the sensibilities of those assembled” at the synagogue, and not wishing to be seen as rude and ungrateful, Loury “opted not to raise the subject of the war at all.”

He continues as follows (emphasis added):

But I didn’t avoid the topic out of mere politeness. Up to that point, on my podcast, The Glenn Show, I had merely dropped hints that I was uncomfortable with America’s role in the war. But I was afraid of what taking an explicit, full-throated position critical of Israel’s military response would do to my reputation. I was wary that the issue was so charged that I could lose friends over it. And I knew that some readers and viewers of my comments would infer the worst: that I was taking sides against the Jewish state, and so against the Jewish people. These perceived pressures—and some of them are more than merely “perceived”—have led me to approach the topic tentatively, and sometimes even to hold my tongue…

Whatever I may say about Gaza—whether I say I believe the IDF’s action to be heinous crimes or to be fully justifiable defensive measures or something in between—this will spur my audience to infer information not explicitly stated about my ostensibly concealed personal beliefs and about my character… Thus, if I say, “Israel must go to whatever lengths it deems necessary to defend itself,” some will infer that I hate Palestinians, or care little for their safety. By contrast, if I say, “Israel must bear some moral responsibility for the high number of dead noncombatants,” some will infer that I hate the Jewish people, or care little for their safety. I can protest that the inference is untrue but in either case such denials do little to exonerate me in the eyes of those who take such statements to be nothing but the acceptable public face of nefarious private beliefs. This is particularly so if others, known to have nefarious beliefs, are making similar statements.

Here’s another adverse inference: that I am a dupe or pawn who doesn’t know his own mind; that I’ve been hoodwinked by the public relations campaign of one side or the other of this conflict. Here is yet another inference: that I seek to curry favor with supporters of the side I’m defending; or that my private beliefs are misaligned with what I say publicly…

The stakes are enormously high for those directly enmeshed in the conflict. They seek allies wherever they can find them. As a result, the ad-hominem-inferential heat has been turned up for those of us lucky enough to be able to comment from the sidelines rather than to experience the front lines. Anyone talking about Gaza, whatever the nuances of their argument, is sorted into the “friend” pile or the “enemy” pile and is treated accordingly. There is no third pile.

This is our ever-present condition when speaking about any controversial issue in public. But there is a difference between being branded an “enemy of high corporate taxes,” say, and an “enemy of the Jewish people.” Plenty of respectable folks have no problem wearing the former label, but no respectable folks should want to wear the latter. In fact, wanting to wear that label ought to exclude one ipso facto from the realm of respectability. We can debate how to tax corporations, but there should be no debate at all about the humanity of the Jews. That is why adverse ad hominem inferences about critics of Israel’s conduct in this war—the conclusion that the critic harbors Jew-hatred—can be so damaging.

This is my point, then. I am not an enemy of Israel, but I have problems with what its military is currently doing and with its influence on American foreign policy. I am certainly not an enemy of the Jewish people… I loathe the antisemites using protest against Israel to gin up hatred for Jews, but I admire those sincere protestors and activists who want to put a stop to the unnecessary bloodshed and an end to the humanitarian crisis.

Having just read the preceding paragraph, some of you, if you were not already decided, have sorted me into one pile or the other. This leaves me to perform a calculation of my own: at what point does the cost of speaking my mind outweigh the benefit? At that Palm Beach synagogue, I performed that calculation and determined that the personal costs of speaking my mind outweighed the benefits. I kept my mouth shut about Gaza. I have felt shame about that silence ever since.

This last sentence is what I was referring to when I said that the preservation of social esteem by the maintenance of public silence is eventually paid for in the coin of self-respect.

One of my favorite novels of all time is The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man by James Weldon Johnson, originally published anonymously in 1912 and acknowledged by the author in 1927. It tells the story of a biracial man (with a black mother and white father) who decides to pass as white for personal safety and some degree of material comfort. Neither his wife nor his children are aware of his deception. Late in life, while witnessing the incipient struggle for civil rights, the narrator starts to feel that he as been a coward and a deserter, and becomes “possessed by a strange longing” for his “mother’s people.” He is moved by the “small but gallant band of colored men who are publicly fighting the cause of their race” and comes to the following realization:

Even those who oppose them know that these men have the eternal principles of right on their side, and they will be victors even though they should go down in defeat. Beside them I feel small and selfish. I am an ordinarily successful white man who has made a little money. They are men who are making history and a race. I, too, might have taken part in a work so glorious.

My love for my children makes me glad that I am what I am and keeps me from desiring to be otherwise; and yet, when I sometimes open a little box in which I still keep my fast yellowing manuscripts, the only tangible remnants of a vanished dream, a dead ambition, a sacrificed talent, I cannot repress the thought that, after all, I have chosen the lesser part, that I have sold my birthright for a mess of pottage.

The analogy between self-censorship and racial passing is far from perfect, of course, but holding one’s tongue on highly contentious issues allows one to blend into an amorphous crowd with ambiguous positions and provides a measure of material and psychological comfort. It is entirely understandable. We all indulge in it to some degree. But it can inflict a substantial personal cost.

But what about the social cost of self-censorship? Let’s return to Loury’s chapter:

The risk of self-censorship… is not so much that our public intellectuals and political leaders will be repressed, but that private citizens will be. If we cannot know what our friends, family, neighbors, and community truly think, because they fear reprisal, we cannot know ourselves. Social life abhors a discursive vacuum, and where self-censorship imposes diffident silence, true evil can creep in. We need only look to the former Soviet nations to see how silence, enforced by fear, will be filled by suspicion, betrayal, and the shattering of social bonds.

We can calculate the cost of speaking out. But how can we possibly calculate the cost of shutting up? We can enumerate the catastrophes that have resulted when ordinary people in a position to stop a great wrong instead did nothing, believing they could not bear the cost of speaking out because they could not be sure they had the support of their fellows. It could be argued that those who remained silent did not know the price of that silence until it was already too late. One wonders what tragedies could have been averted, how much suffering avoided, had everyone known each other’s minds.

There is a reason why certain opinions are often met with censorious opposition: it’s an efficient way to control the discourse. You can’t silence everyone. But then, you don’t have to. Destroy the reputations of a few prominent people, and everyone who agrees with them will fall into line. Level the ad hominem attack—“He thinks that because he’s antisemitic”—and the substantive issues get drowned out while an unpopular speaker struggles to defend not his ideas or thoughts, but his very person. A pall of suspicion falls over him. He’s sorted into one pile or another.

Once that sorting has taken place, no amount of self-exculpatory pleading can undo it. When a person’s character is assassinated, it tends to stay dead, and not even the corrective of historical hindsight can revive it. Silence, as a self-defensive measure, has its appeal. But those of us who defend free speech have a special responsibility to speak our minds openly when we feel—when we know—that the others who share our views will not or cannot do the same. We’re inevitably placed in a vulnerable position, for even audiences who would affirm the necessity of speaking out in principle sometimes attempt to squelch the speech they disdain.

One way to squelch speech that you disdain is to assert that it is hate speech, beyond the acceptable bounds of public discourse. If Zionism is equated with racism, or anti-Zionism with antisemitism, a lot of conversations are instantly halted.2

It is no surprise, then, that the Israel-Palestine conflict is the single issue on which the greatest degree of self-censorship is practiced by faculty in higher education. At Columbia, for example, 89 percent of respondents in a recent survey confessed to censoring their views on this topic. No other issue comes close—affirmative action is in second place with 42 percent.

Nobody wants to be seen as a bigot, and on this issue, there is no third pile.

Unless, of course, one has what Loury calls natural cover:

Standing to address an issue is restricted to a certain class of persons who have what I will call “natural cover.” These are people who, because of their group identity, are not immediately presumed to have malign motives for expressing themselves in a potentially offensive way… The censorship in these cases is partial; those who have “cover” express themselves freely; those who lack it must be silent. When the combination of an ascriptive trait with an offending expression is necessary to mark the speaker as “bad,” words spoken in mixed company have a meaning-in-effect that is contingent upon who has spoken them.

Loury has natural cover when he speaks about affirmative action or reparations, but not when he speaks about Israel’s actions in Gaza. He cannot credibly be accused of anti-Black racism, but has to labor to defend himself from charges of antisemitism.

The prolific and influential economist Ariel Rubinstein, when speaking about the country of his birth and citizenship, does have natural cover.3 His parents migrated to the region from Poland, at a time when many of their relatives were facing certain death. He cast his first vote in 1969 for a party on the extreme right that he likens to that led by Ben-Gvir today. But by 1977 he had become a staunch critic of the settler movement and a founding member of the Movement for a Different Zionism. A year later he was among the organizers of the 1978 Officer’s Letter, which argued that the expansion of settlements beyond the Green Line would put at risk the dream of a Jewish democracy. It is a dream to which he remains fully committed.

In a recent article in Haaretz (joinly written with Motty Perry) Rubinstein weighed in on the current conflict as follows:4

There are those who believe that the flattening of Gaza will convince the Palestinians to relinquish their national aspirations. Is that so? We know of one people whose national aspirations only grew stronger after losing one-third of its sons and daughters. We also know a neighboring people, less “chosen,” that has weathered blow after blow and only become more resolute. According to Palestinian health officials and the United Nations, over 45,000 people in Gaza have died in the 14 months of the war – nearly 2 percent of the territory's prewar population. Nine in 10 Gazans have been driven from their homes. Nonetheless, the elders of Gaza are not surrendering and are not begging for the opportunity to serve the renewed Jewish settlements in Gush Netzarim. Isn't it true that vengeance primarily breeds vengeance?

We're terrified of the future. Horrible things tend to eventually come to light. In the coming years, we'll encounter soldiers who break the silence, shell-shocked and ridden with guilt. One will leave a suicide note, another will remove his kippa and tzitzit, and another will write a sequel to S. Yizhar's 1949 novel “Khirbet Khizeh.” In the end, what isn't known comes to light. And the sin of covering up is added to the crime.

Nakba 2 is transpiring in the Gaza Strip. Two million people have been driven from their homes, but nary a word of complaint or protest can be heard in Israel. Some Israelis are swept up in messianic dreams of a Jewish Israel “from the sea to the river” (and beyond). The state is systematically encroaching on Arab areas in East Jerusalem and the West Bank. In soccer stadiums and on TV screens, Arabs are viewed as two-legged beasts. Nakba 3 is knocking at the door.

Both of us were born here, remain here of our own free will and have never even considered the idea of emigrating. We're certain that we will continue to live here till our dying day. Nakba 3 will not only be a catastrophe for the Palestinians. It will also sound the death knell for the State of Israel we’d like to bequeath to future generations.

The events in the Middle East since the October 7 massacre are described as the butterfly effect. We envision the gorilla effect. The gorilla stands before us, waving its arms urgently trying to draw our attention. However, delusions and indulgence in the pleasures of life blind us to its presence. But the gorilla is not going anywhere and it threatens to stain Jewish history forever.

Rubinstein expands on these comments in a recent conversation with Larry Kotlikoff, where he states that his greatest fear is not of terrorist attacks or military strikes, but of a transformation of Israeli society into one that flies the same flag but does not have the same meaning. He understands, of course, that his position is not widely held in the country, and seems resigned to the possibility that it may never win the day.

I have little scholarly expertise on these matters, and no natural cover in discussing them. But democracy requires citizens to make highly consequential decisions based on partial information and imperfect understanding. The scale of death and destruction in Gaza is so staggering, and the role of the United States so central, that we Americans must confront the question of whether it is ethically defensible. I have quoted at length here from two people who are known to me and whose judgement I trust. I am open to other perspectives and will continue to learn.5 But I can no longer avert my gaze.

For instance, the argument by Jake Klein that support of Zionism is inconsistent with a principled objection to identity politics cannot even be made.

I have had many warm and fruitful conversations with Rubinstein over the years, and his research (with Martin Osborne) on procedural rationality has had a clear and significant impact on my own work.

Perry was also an organizer of the 1978 Officer’s Letter.

Over the past year or so I have tried to absorb as much information about this conflict as time permits, listening for hours to conversations and debates involving a range of viewpoints, from Benny Morris, Eli Lake, and Steven Bonnell offering one set of perspectives and Mouin Rabbani, Rashid Khalidi, and Norman Finkelstein offering another.

Great piece. I’m too uninformed to suggest sensible American policy in Gaza, but I can’t help but think about how the ‘unnatural’ cover of anonymity plays into this. Adverse inference might in part explain why anonymous opinions have surged—technology makes it easy, and anonymity removes the personal cost of speaking out.

But this might also suggest why controversial anonymous dialogue is so unconvincing—because the participants offer up no reputational collateral. Persuasion from anonymous actors depends largely on the sheer volume of opinions expressed. Conversely, by speaking with the backing of your real identity, you indicate that you’re willing to stake your reputation on your argument, increasing its singular potency.