Back in 2003, a Pentagon office led by Admiral John M. Poindexter proposed the creation of “an online futures trading market… in which anonymous speculators would bet on forecasting terrorist attacks, assassinations and coups.” The effort met with immediate bipartisan resistance in Congress, and was scrapped almost as soon as it came to light. Concerns were raised that terrorists could participate in such markets, either to profit directly from impending actions, or to mislead intelligence agencies by betting against events that they were in the process of planning. The idea was described as “morally repugnant and grotesque,” and it cost Poindexter his job.

I wrote about this episode at the time, concluding that the eventual emergence of such markets, with or without government involvement, was inevitable. And, indeed, here we are:

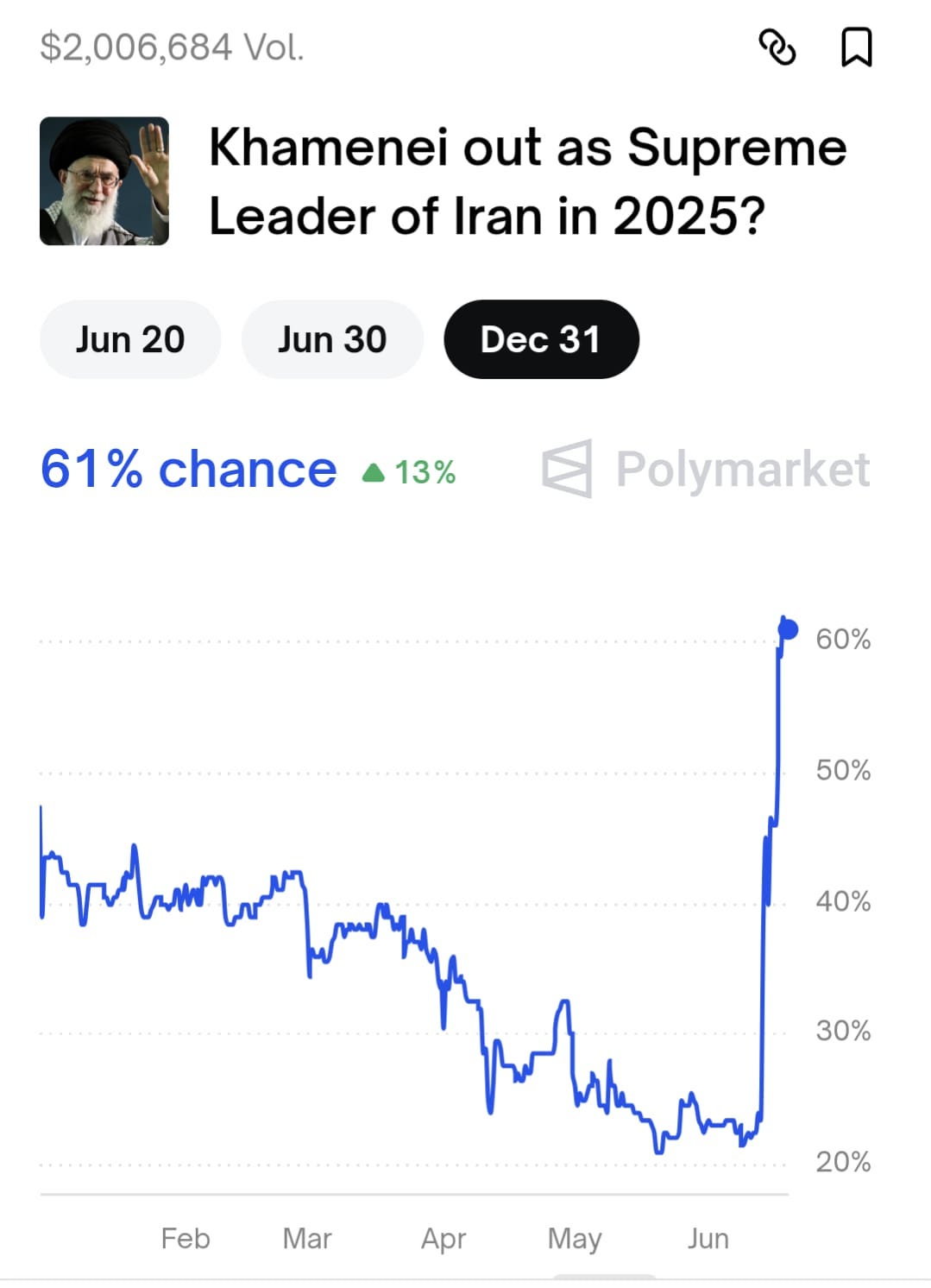

This is just one example. Millions are currently being wagered on whether Iran will face US military action, a coup attempt, or a major cyberattack, and on whether there will be a strike on Israel's Dimonah nuclear base.

These are markets in which people with inside information (including state actors) can make a lot of money without risk of exposure, since the exchange is crypto-based and doesn’t have a know-your-client requirement. The insiders don’t have to be primary decision makers, they just need to have access to closely-held information. And they can trade on impending announcements that will move markets, even if these statements are later withdrawn and threatened actions fail to materialize. We have seen this already with repeated announcements and reversals concerning tariff policy.

As it happens, there is some fairly strong evidence that insiders have been trading ahead of military strikes, on at least three occasions. The most recent case involves an account that was created and funded about one day before Israel’s June 13 attack on Iran, started accumulating contracts at scale about twelve hours before the bombing began, made $134,000 in profits, then cashed out immediately and disappeared from the exchange.

It might be argued that the participation of insiders leads markets to generate more accurate forecasts at greater speed. But this neglects the effects of insiders on the behavior of others. The suspicion that any given price move may be driven by inside information can lead outsiders to jump on trends with greater frequency and force, giving rise to momentum effects and heightened volatility.1 I suspect that this is what happened in the papal conclave market, leading to a sharp (and erroneous in retrospect) response to white smoke.

There is a more serious problem to consider—the presence of such markets can affect the objective probability with which the underlying events occur. In fact, this was one of the claims made in defense of the original proposal by Poindexter—he argued that markets could serve as an early warning system that could help to thwart attacks.2 But an effect in the opposite direction also seems possible, an organization or state actor could accumulate a large position before executing a plan of attack, or simply engage in chatter that moves markets and allows it to cash out at a profit.

This is a strange new world we are living in, where the likelihood of a coup or military strike can be tracked in real time, with countermeasures responding to and being reflected in market prices. But the horse is out of the barn—there is nothing that can be done in the foreseeable future to prevent the proliferation of crypto-based prediction markets on any event imaginable. We can, however, try to better understand the system rising up around us and the incentives it creates, with feedback loops between subjective beliefs and objective probabilities, and avenues for the powerful and well-connected to leverage information and amass wealth.