Towards an Inclusive Patriotism

John McWhorter has a recent piece in the New York Times in which he discusses the significant and lasting influence of the pathbreaking 1921 show Shuffle Along on the evolution of the Broadway musical:

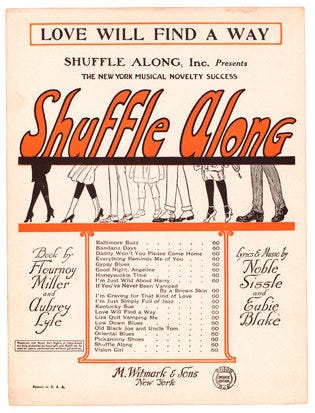

I have, over the transom, received the paperback edition of a book that escaped me last year, to my regret. It is “When Broadway Was Black” by Caseen Gaines, and it is important first in that it recounts the story of a Black-created musical of 1921, “Shuffle Along,” that made some serious noise and may just have invented the modern Broadway musical. It was created by Black men, the pianist and composer Eubie Blake and the singer and lyricist Noble Sissle, and the cast was all Black.

It wasn’t the first Black musical on Broadway… but it was the first one that really landed in an epic way. It backed up traffic in front of its theater, sparked the career of Josephine Baker — who started out in its chorus line — and nearly 100 years later, in 2016, inspired a Broadway musical saluting its creation.

But “Shuffle Along” and its genesis are important to know about for reasons beyond the musical’s success at the time. Broadway wasn’t Black for a mere spell after “Shuffle Along” — it became Black permanently.

Before this… Broadway’s music was, for the most part, quite white in a sense similar to what one might mean today. It toodled, it cooed, it marched. Sometimes it had a touch of ragtime in its step. But little of it stood out in an artistic sense. America had yet to develop a general, default theater music style it could be proud of internationally… “Shuffle Along” is what changed this: It inaugurated what we now take for granted, the electricity of the Broadway sound.

He goes on to discuss the influence of this musical (and Jazz more generally) on the styles of George Gershwin and other “top-drawer” composers of the time, concluding that the “Broadway sound, despite how “white” we may classify it as today, represents one of many Black contributions to what America is.”

Reading this essay brought a number of thoughts to mind.

To begin with, I remembered that I had seen the 2016 adaptation of Shuffle Along, with Audra McDonald transcendent in the role of Lottie Gee. This was part revival and part back-story, featuring much of the original song list. The choreography was by Savion Glover, whose breathtaking performance in Bring In da Noise, Bring In da Funk I had been fortunate enough to witness many years earlier.

McWhorter’s article also reminded me of a brilliant essay by Ralph Ellison that I have mentioned in an earlier post on the need for a dynamic and inclusive patriotism. Ellison’s subject was literature rather than theater, but the parallels are striking:

If we can cease approaching American social reality in terms of such false concepts as white and nonwhite, black culture and white culture, and think of these apparently unthinkable matters in the realistic manner of Western pioneers confronting the unknown prairie, perhaps we can begin to imagine what the U.S. would have been, or not been, had there been no blacks to give it—if I may be so bold as to say—color.

For one thing, the American nation is in a sense the product of the American language, a colloquial speech that began emerging long before the British colonials and Africans were transformed into Americans. It is a language that evolved from the king's English but, basing itself upon the realities of the American land and colonial institutions—or lack of institutions, began quite early as a vernacular revolt against the signs, symbols, manners and authority of the mother country. It is a language that began by merging the sounds of many tongues, brought together in the struggle of diverse regions. And whether it is admitted or not, much of the sound of that language is derived from the timbre of the African voice and the listening habits of the African ear… Its flexibility, its musicality, its rhythms, freewheeling diction and metaphors… were absorbed by the creators of our great 19th century literature even when the majority of blacks were still enslaved. Mark Twain celebrated it in the prose of Huckleberry Finn; without the presence of blacks, the book could not have been written. No Huck and Jim, no American novel as we know it. For not only is the black man a co-creator of the language that Mark Twain raised to the level of literary eloquence, but Jim's condition as American and Huck's commitment to freedom are at the moral center of the novel.

In other words, had there been no blacks, certain creative tensions arising from the cross-purposes of whites and blacks would also not have existed. Not only would there have been no Faulkner; there would have been no Stephen Crane, who found certain basic themes of his writing in the Civil War. Thus, also, there would have been no Hemingway, who took Crane as a source and guide.

Finally, McWhorter’s essay reminded me of the contribution by Wesley Morris to the 1619 project. The tone is different, but the substance is much the same:

Americans have made a political investment in a myth of racial separateness, the idea that art forms can be either “white” or “black” in character when aspects of many are at least both. The purity that separation struggles to maintain? This country’s music is an advertisement for 400 years of the opposite: centuries of “amalgamation” and “miscegenation” as they long ago called it, of all manner of interracial collaboration conducted with dismaying ranges of consent… Since the 1830s, the historian Ann Douglas writes in “Terrible Honesty,” her history of popular culture in the 1920s, “American entertainment, whatever the state of American society, has always been integrated, if only by theft and parody.” What we’ve been dealing with ever since is more than a catchall word like “appropriation” can approximate. The truth is more bounteous and more spiritual than that, more confused. That confusion is the DNA of the American sound.

I’m not sure that McWhorter will appreciate this last comparison, given the frequency and ferocity of the criticism that he and Glenn Loury have leveled against the 1619 Project on Glenn’s podcast. They view it, with some justification, as being identitarian and divisive. But I have to admit that when I first encountered the essays in that collection, they struck me as a long overdue attempt to forge a more inclusive patriotism. One that sees the origins of American society not in the nation’s founding documents, but in the culture that gave rise to them. A culture that had already been incubating for a century and a half before the nation itself was born. A culture that was heavily reliant on the European enlightenment, but also shaped by powerful African influences at its roots.

In my last conversation with Glenn on his show, I pointed out the absurdity of thinking of Indian society as having its origins in 1947, when independence from Britain was finally attained. The event was hugely consequential, of course, but the nation’s culture was not transformed overnight. By the same token, 1776 represented a sharp change in direction but hardly an erasure of what came before it. If one separates the wheat from the chaff, and looks past what might be grating or offensive, there is some value to be found in this reconceptualization of America’s meaning. One in which the founding documents and their authors can be celebrated without being idealized, or critiqued without being vilified. One in which they are seen as novel products of an existing hybrid culture. McWhorter and Ellison and Morris, while coming at it from different directions, are all giving us glimpses of the same truth.