The Polymarket Raid

Federal agents raided the home of Polymarket founder Shayne Coplan yesterday, apparently on the grounds that the company was operating “as an unlicensed commodities exchange, allowing users in the United States to place bets in violation of a settlement with the U.S. government.”

The settlement in question was reached in January 2022, and requires the company to prevent American nationals and residents from trading on its platform. However, being a crypto-based exchange, Polymarket doesn’t actually know the identities of all those who have funded accounts and are buying and selling contracts on its site. The best it can do is to block users based on their suspected location (or based on their suspected nationality if this can be deduced from their login credentials).

If you try to create an account while in the United States, and do not take effective measures to disguise this, you will encounter the following screen:

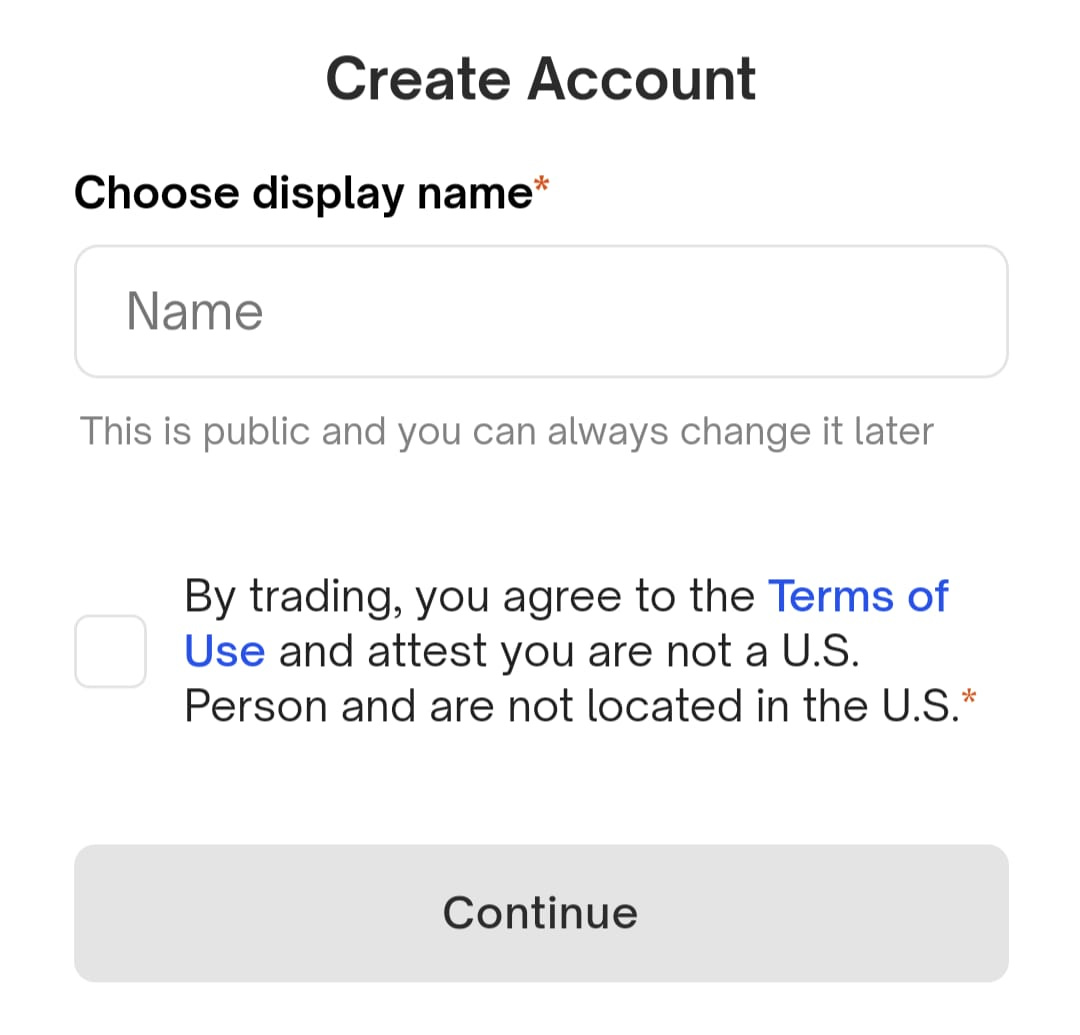

However, using a virtual private network (to disguise location) and logging in using MetaMask or some other cryptocurrency wallet bypasses the above screen and allows you to fund an account, subject only to a declaration that you are not a U.S. national or resident:

Perhaps large traders have to take additional steps to authenticate their location or residency at some point, but this seems not to apply to all traders.

The raid seems entirely pointless to me, for a couple of reasons.

To begin with, any federal case against Polymarket is likely to be dropped within months under the incoming administration. More importantly, if the company is to continue operating as a crypto-based exchange on which traders can remain anonymous, it will be impossible to reliably prevent American nationals and residents from participating. And if this fact alone is enough to make operation unlawful, then the company will simply move offshore, and will face even fewer incentives to screen out American nationals and residents.

I understand why regulators are concerned about betting on political contests—the objective probability of an election outcome depends on subjective beliefs about what is likely to happen. Pessimism about a campaign can become self-fulfilling, through effects on enthusiasm, volunteer effort, donations, and turnout. And large bets on prediction markets can move prices to some degree, and thus affect perceptions of viability and momentum. This is why campaigns are selective in releasing internal polls, and why the management of expectations is considered so vital.

But the solution here is not enforcement that will eventually prove toothless in any case, but rather the promotion of competition, especially through the establishment of regulated exchanges. This is why I supported the application of Kalshi to list contracts referencing election outcomes. Having a regulated market competing with crypto-based and offshore exchanges provides a useful standard of comparison, especially if one is concerned about large bets influencing voter beliefs.

A company spokesman described the raid as a case of “obvious political retribution by the outgoing administration.” Kevin O’Leary (of Shark Tank fame) thinks otherwise. But either way, the actions of regulatory and enforcement agencies with respect to prediction markets over the past couple of years have lacked coherence and defied logic.