The Limits of Arbitrage

Something quite interesting has been happening on prediction markets over the past month, especially in comparison with the forecasts emerging from statistical models based on opinion polls.

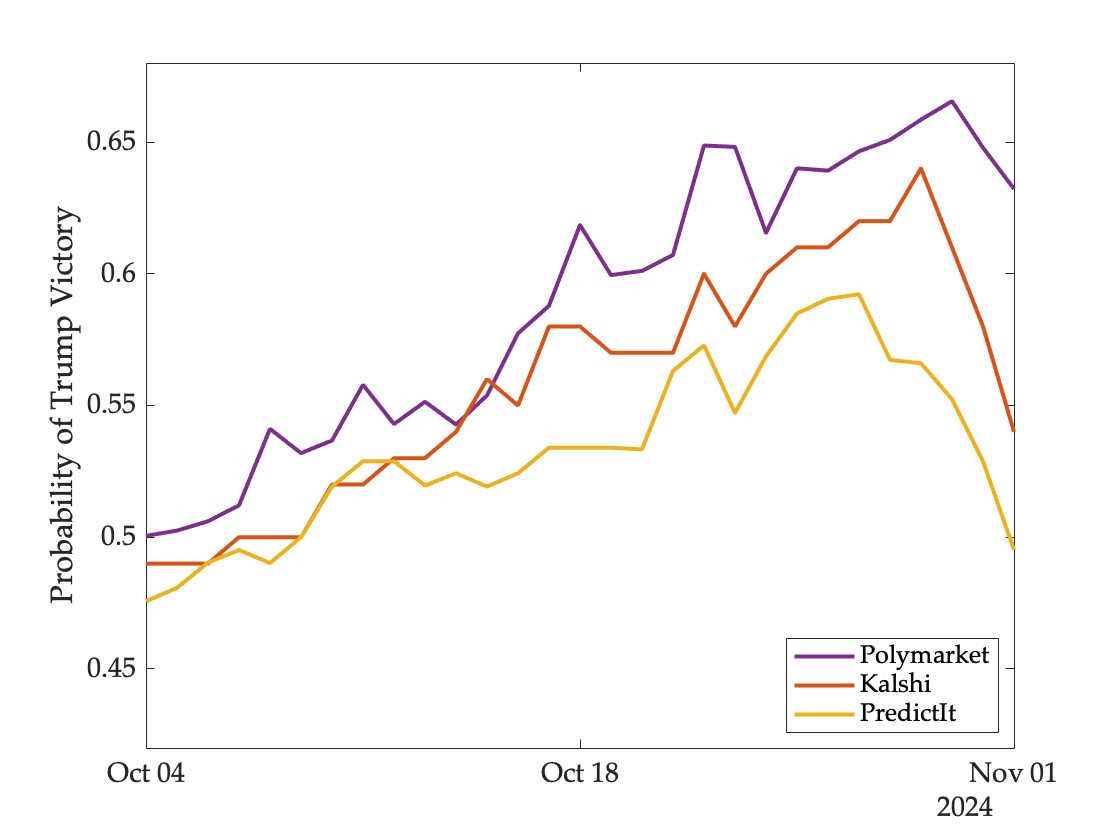

Here are the implied probabilities of a Trump victory on three markets since October 4 (the day that Kalshi first listed its presidential election contracts):

The markets all saw a coin flip race in early October, then rose sharply with crypto-based Polymarket leading the way, peaking at around 67 a couple of days ago. There has been a reversal since then, with PredictIt essentially back to a coin flip.

Meanwhile statistical models have been stable, giving Harris a slight edge early in the period, then shifting towards Trump, but remaining within a relatively narrow band throughout (I’ve kept the scales of the two graphs the same for ease of comparison):

How should one interpret these movements?

As I explained in a recent conversation with Glenn Loury, markets are tied together by arbitrage—if one of them moves sharply in a given direction then others must follow. The logic is simple. If the Trump contract is trading at 60¢ on one market and 50¢ on another, one can bet against him on the first for 40¢ and against his opponent on the second for 50¢, thus buying a dollar for 90¢. If many try to exploit this opportunity at scale, the price of the Trump contract will fall on the first market and rise on the second, until prices have converged enough to make the trade unappealing.

Since the exchanges are independent, someone executing this strategy would tie up their money for weeks and possibly months. The contracts also vary slightly in language and resolution criteria, so the approach is not entirely without risk. But still, the effect exists and you can see it in the market movements—a surge of large bets on Trump in early October sent his Polymarket contract skywards and the other markets followed with a bit of a lag.

More interestingly, it has been PredictIt that has led the decline. This exchange is dwarfed by the others in volume, and is operating under strict restrictions. No more than 5,000 traders can simultaneously hold positions in any contract, and each of them is limited to a position size of $850. These constraints—and the resulting low volume—have led many to dismiss its value as a forecasting mechanism.

But I have argued for a while now that the position size limit has the potential to improve forecasting accuracy, by ensuring that no single trader or small group can come to dominate the market. This prevents the beliefs of a few highly confident and deep-pocketed individuals from having a disproportionate impact on price, and preserves a valuable wisdom of crowds effect.

The evidence suggests that the bets responsible for sending the Polymarket price rocketing upwards were made by someone simply trying to make money, and were not motivated by an attempt to manipulate the price. Incentives for manipulation exist because elections are not like solar eclipses—subjective beliefs can affect the objective probabilities of various outcomes. Pessimism can be self-fulfilling through its effect on morale, effort, fundraising, and turnout, so engineering pessimism about an opponent can be profitable.

Similarly, optimism can end up justifying itself. This is why campaigns are very selective in releasing internal polls. It is also why the market movements in favor of Trump have been heavily promoted by his supporters on social media, and indeed by the candidate himself. At the margin, this may have had an impact on the behavior of some voters.

What are the policy implications of this?

Trying to shut down these markets is not the solution, and would be doomed to failure in any case. Offshore and crypto-based exchanges are largely beyond the reach of regulators. It is useful to have a regulated competitor such as Kalshi operating in the US; despite the arbitrage effect it offers a meaningful standard of comparison. There are few large traders eligible to operate on both Kalshi and Polymarket, which allows for some independence in price movements.

But the best defense against market-driven changes in voter sentiment may actually be the small-scale, highly restrictive PredictIt, which is somewhat insulated from arbitrage by design. Much can be done to improve its performance, starting with changes in its absurd and punitive fee structure. But this exchange should be protected by regulators, and should receive a lot more interest from the media.

> insulated from arbitrage by design

Wouldn't this too limit the wisdom of the crowd effect? Arbitrage allows information from one market flow to another, essentially combining their crowds.

Fantastic work Rajiv, thanks! Would you be willing to make comparisons with other sources, possibly by exchanging data with us? I'd love to see a comparison with bias-corrected estimates based on X polls, e.g., of the % of support for candidates [1], or our upcoming estimate of the probability of victory. Based on my personal observations, prediction markets exaggerate the advantage of leading candidates in comparison to the % of public support. For instance, bias-corrected estimates based on X polls show temporal trends resembling prediction markets, but less pronounced. Both sources showed a drop in support for Trump after the debate, increase at the beginning of October, and a drop between October/November [1, 2]. Perhaps there is a rational explanation for that.

[1] https://socialpolls.org/#/timechart

[2] https://www.threads.net/@przemyslslaw/post/DBjhL0koRmP