The Detection of Wash Trading

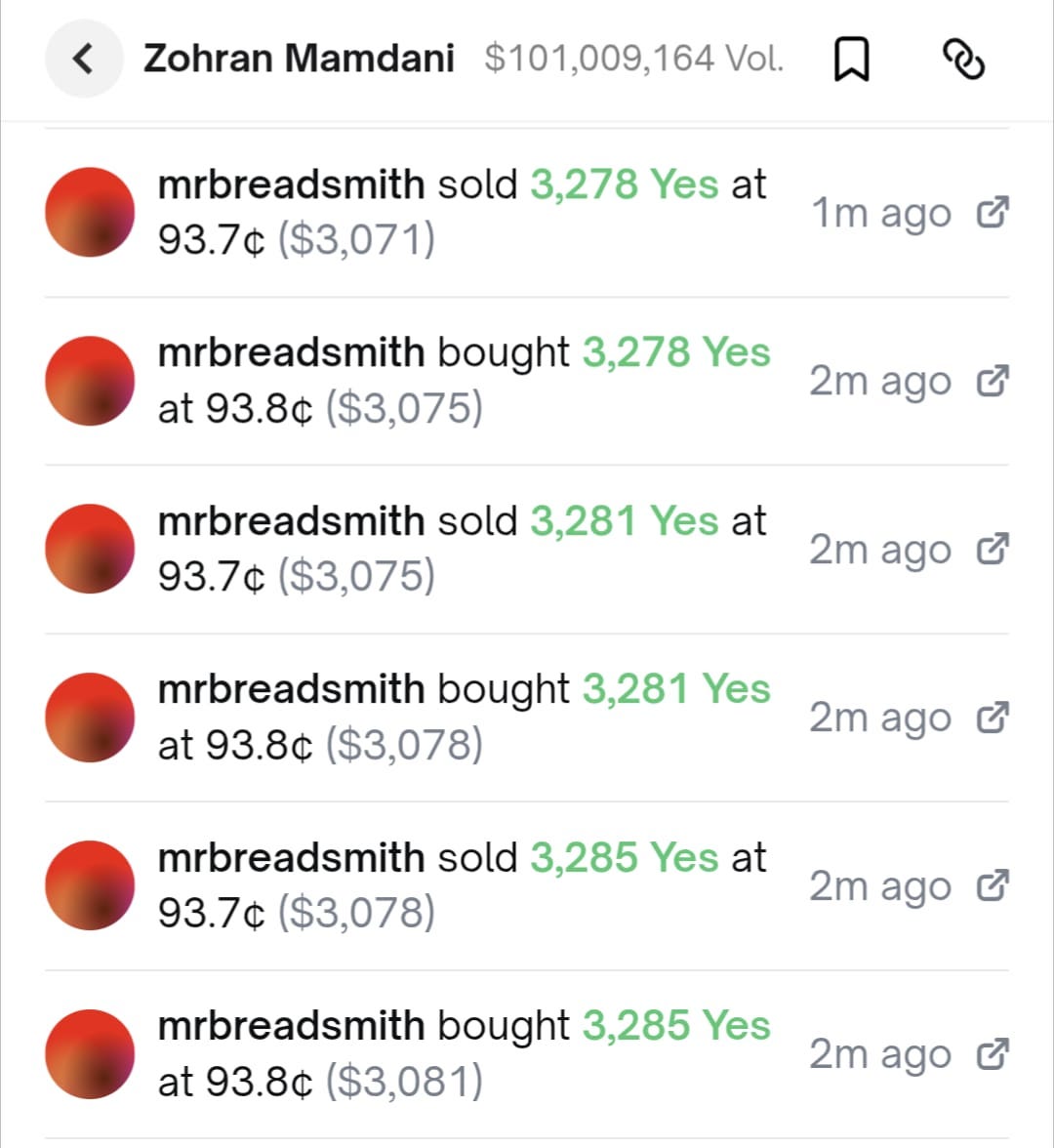

Consider the following set of trades executed in quick succession on Polymarket at around 6pm on November 1, just a couple of days before polls opened on election day:

This is just a small sample of a string of very similar transactions executed by the same trader at around the same time. At first glance they appear to make no sense—each purchase is followed quickly by a sale at a price that is a tenth of a penny lower, resulting in a guaranteed loss. It appears that the trader is willing to incur relatively modest losses in order to boost recorded volume by a substantial amount.

But is the trader actually incurring losses? That would depend on the counterparties to these trades. If all wallets involved were engaged in a collusive exercise to boost volume, losses for some would correspond to gains for others, netting out to zero for the group as a whole.

This would be an example of wash trading, defined as the practice of entering into “transactions to give the appearance that purchases and sales have been made, without incurring market risk or changing the trader’s market position.” Such activity is prohibited by law on regulated exchanges in the United States, and can be subject to significant sanctions.

But how can one reliably detect collusive clusters of accounts that are engaged in wash trading? To see the difficulty, suppose one were to discover that each of the trades shown above had the same counterparty. This alone would not be decisive, because market makers often place orders to buy and sell the same security, hoping to profit from the spread. Such activity is both lawful and routine. If some trader is intent on filling the posted orders at a loss, a market maker will gladly accommodate them for a profit. So checking to see if the counterparties to a suspected wash trader happen to all be the same is not enough—they could all be the same market maker.

What one needs to do is to look at counterparties to those counterparties across all their other transactions. Like wash traders, market makers open and close positions rapidly, and avoid building up large positions that would expose them to substantial risk.1 But there is one major difference between them. Wash traders trade with other wash traders in their collusive clique, while market makers neither know nor care who their counterparties are. In fact, market makers seldom trade with other market makers.2 That is, if one were to represent traders as nodes and transactions between them as edges in a network, wash traders would exhibit homophily while market makers exhibit heterophily.

This is the central idea explored in a paper that was posted online last week, on which I am a co-author. The lead author is Allen Sirolly, an exceptional doctoral student, and other co-authors are Hongyao Ma and Yash Kanoria. There has been a fair amount of media coverage and online commentary on the paper, but this has focused largely on its empirical claims rather than on the core theoretical contribution. Our primary goal in writing the paper was to introduce a novel method for the detection of wash trades that could identify not just the obvious cases visible to a casual observer, but also more sophisticated schemes that might otherwise escape scrutiny.

The proposed algorithm is modular, with an initialization stage followed by an iterative network-based redistribution stage. At initialization, we assign to each wallet a score based on its propensity to open and close positions repeatedly. At the redistribution stage, we update each wallet’s score based on the scores of its volume-weighted counterparties. This is done repeatedly until we achieve approximate convergence. Those wallets left with scores above a specified model parameter are then identified as wash traders. The process is parameter-dependent but robust to changes in parameters.

You can see the process at work in the following figure, which appears as Figure 5 in the paper. Each node corresponds to a wallet, with area proportional to the square root of share volume. Many wallets with high scores at the initialization stage (shown in red) are dropped at successive iterations at the redistribution stage, leaving wash traders identified with high confidence after three iterations.

The three wallets flagged at the bottom left all have similar names: MAY20, MAY175, and MAY176. These are part of a cluster of 200 with names all starting with MAY, trading almost exclusively with each other. These wallets collectively traded over 116 million shares and generated more than 113 million in dollar volume, but ended up with an aggregate loss of just $57.86. One of these was MAY117, an account that bought and sold over a million shares across 33 markets over several months and ended up with profits of precisely zero.3

The modular nature of the algorithm allows for choosing different criteria at the initialization stage (such as the number of transactions per unit time) and then using the redistribution stage to identify accounts that trade almost exclusively with others exhibiting similar behavior. The approach can be easily applied to other markets for which transaction-level data are available, and it could be useful to exchanges interested in rooting out wash trading.4

Any algorithm of this kind, once published and implemented, is likely to result in strategic responses by wash traders that better allow them to evade detection. Ideally one would want to design a system that is not vulnerable to such gaming, but whether or not this ideal is even attainable remains an open question.

We consider the simplicity and interpretability of our algorithm to be a strength, but understand that ours is not the last word. There are other ways to approach the problem, and the problem itself is important. Trading volume is among the most commonly used measures of market participation and conviction, and wash trading makes it imprecise and less meaningful. Developing a transparent and modular detection algorithm—rather than the specific empirical claims about a particular exchange—is the enduring contribution of the research.

The risk comes from adverse selection—significant new information could arrive while orders on both sides of the market are resting in the order book, in which case the orders that get snapped up by other traders are precisely those that would inflict losses on the market maker. The general problem of market maker pricing in the face of adverse selection has been studied in classic papers by Glosten and Milgrom and Kyle.

Each trade in a continuous double auction involves a liquidity provider and a liquidity taker, so while liquidity providers compete with each other in the placement of bids and offers, they seldom transact with each other.