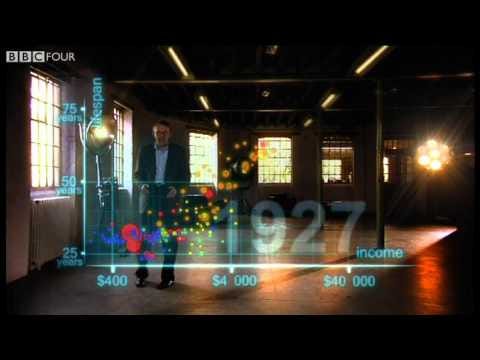

Global Health and Wealth over Two Centuries

Here is a story in four minutes of remarkable divergence followed by rapid convergence in health and wealth across nations over the past two centuries (h/t David Kurtz)

Where the entire world was clustered in 1810 only sub-Saharan Africa remains. But even here there are profound stirrings of change.

I suspect that someday soon animations such as this will replace the soporific tables and charts than now appear as motivating evidence in economic papers.

---

Update (12/6). Pinkovskiy and Sala-i-Martin argue that over the past decade and a half, the nations of sub-Saharan Africa have experienced a dramatic and broad-based decline in poverty and inequality (h/t Mark Thoma):

African poverty reduction has been extremely general. Poverty fell for both landlocked and coastal countries, for mineral-rich and mineral-poor countries, for countries with favourable and unfavourable agriculture, for countries with different colonisers, and for countries with varying degrees of exposure to the African slave trade. The benefits of growth were so widely distributed that African inequality actually fell substantially...

It has often been suggested that geography and history matter significantly for the ability of Third World, and especially African, countries to grow and reduce poverty... Since these factors are permanent (and cannot be changed with good policy), they imply that some parts of Africa may be at a persistent growth disadvantage relative to others.

Yet... the African poverty decline has taken place ubiquitously, in countries that were slighted as well as in those that were favoured by geography and history. For every breakdown... the poverty rates for countries on either side of the breakdown tend to converge, with the disadvantaged countries reducing poverty significantly to catch up to the advantaged ones. Neither geographical nor historical disadvantages seem to be insurmountable obstacles to poverty reduction... even the most blighted parts of the poorest continent can set themselves firmly on the trend of limiting and even eradicating poverty within the space of a decade.

This is consistent with recent observations by Shanta Devarajan, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, and even the much-maligned Gordon Brown.

I have argued in a couple of earlier posts that sub-Saharan Africa may have entered what might be called a zone of uncertainty in which optimistic growth expectations can become self-fulfilling:

History can matter for long periods of time (for instance in occupational inheritance or the patrilineal descent of surnames) and then cease to constrain our choices in any significant way. Once reliable correlations can break down suddenly and completely; history is full of such twists and turns. As far as African prosperity is concerned, I believe that a discontinuity of this kind is inevitable if not imminent.