In my last post I looked at Sweden’s pandemic response and made two observations.

First, it appears that Sweden’s policy choices during the pandemic, which relied largely on voluntary compliance with public health guidance rather than mandates, do not seem to have resulted in superior economic performance relative to its Nordic neighbors. Economic growth in Norway, Denmark, and Sweden followed very similar trajectories over the 2020-2022 period.

Second, there were significant differences across these countries in excess death rates early in the pandemic, with more loss of life in Sweden, but cumulative excess death rates appear to have converged. That is, the Swedish polices affected the timing rather than eventual magnitude of excess mortality. Denmark and Norway were able to postpone excess deaths (relative to Sweden) but not avoid them entirely.

How can these two observations be reconciled? One can explain the economic trajectories by arguing that Swedes voluntarily did what their neighbors were pressured or compelled to do. But this would not explain the pattern of excess deaths. It appears that the main difference between Sweden and its neighbors was the degree to which the most vulnerable populations (the elderly and those with weakened immune systems or serious heart and lung conditions) were protected. The state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell recognized this, while defending Sweden’s overall strategy of reliance on personal responsibility and voluntary compliance.

But there were many other factors at play, including very high vaccination rates in Sweden (perhaps in the shadow of the trauma caused by early excess mortality). Following my earlier post I got a long and thoughtful message from Troy Tassier of Fordham University which discusses some of these issues. I have reproduced his message below with permission.

Hi Rajiv,

I hope that you are doing well. I read your blog post on Sweden with interest today. I have been interested in the “catch-up” in excess deaths by the non-Sweden Nordic countries for a while. It’s very perplexing to me and I haven’t done a really deep dive but I had a few comments that may be of interest to you.

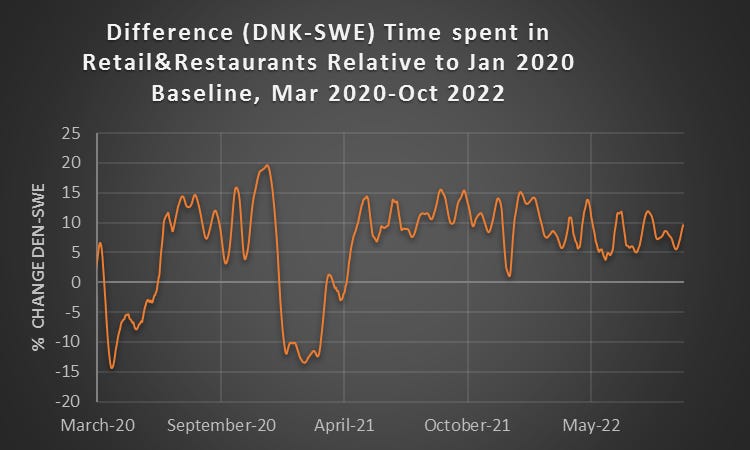

It seems that there is a difference between what I’ll call the “folklore” of Swedish policy and the reaction of Swedish residents. If you look at various mobility metrics (like Google’s mobility data) it appears that the Swedish population didn’t behave all that differently than populations of neighboring countries despite Sweden being less aggressive in terms of its official policy response. Note the two graphs below which are based on Google data gathered from OWiD, smoothed to a weekly average. (Comparisons to other Nordic countries and comparisons using other Google metrics like Time Spent at Home are similar.) Other than the initial pandemic phase in spring 2020 and the winter of 20/21 the Swedish population actually had more conservative behavior than Denmark. They cut back on mobility more than Denmark except for those two periods of time. Because the Swedish population didn’t respond strongly in spring 2020 I think this goes a long way in explaining why Sweden did so poorly in terms of excess deaths. And, it may explain a part of the catch-up by other Nordics (because the Swedish population was actually more careful than the other Nordic populations in 22/23). But I don’t think it can explain all of it. I think it is also interesting that after Sweden did so poorly in 2020 that the population reacted more strongly in future months. Part of me wonders if there was a NYC type effect where things were so bad that people acted strongly in order to avoid a repeat of 2020. So they locked themselves down because of their risk perception from previous experience.

I think point 1 also gives clues as to why Sweden’s economic performance wasn’t appreciably better than its neighbors. The Swedish population didn’t behave all that differently than its neighbors so its economy suffered and then rebounded to a similar degree.

The mobility point above also suggests what I’ll call strong agency effects of populations. Not surprisingly the mapping from policy to behavior isn’t direct. And, like the Sweden graph below, there is evidence that people act to avoid (pandemic) risk without being told to do so—no surprise to an economist that people respond to perceived risk, right?! For instance, Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson suggest that only a small percent of the decrease in economic behavior was due to policy choices/ laws early in the pandemic. And similar to that paper, if you look to things like Google data on time in public transit stations, time spent at home, etc., the majority of the response in March 2020 occurred prior to specific “stay at home” announcements or schools closures. I have a small bit on this concerning NYC and London in a book I have coming out this February. So again, Sweden’s official policies (or lack of policy response) doesn’t mean that Sweden’s population didn’t react. They did and over a large part of the pandemic they responded more strongly than their neighbors despite no policy telling or suggesting that they do so.

All of this still doesn’t explain why the Nordics ended up in the same place as Sweden in terms of excess deaths after 3+ years. I have seen a couple of possibilities suggested (other than the obvious—it was going to happen no matter what policy choice was made and the public health measures implemented in 2020 just delayed the inevitable):

I don’t have a good cite off hand for this but I have been part of conversations suggesting that Sweden did a much better job at getting vaccines to its elderly and most vulnerable populations. And they did this more quickly than their neighbors. This suggests that the catch-up in excess deaths may have been because Sweden’s vaccine policy was more responsive than their neighbors. Which again is a different story than the one that dominates public perception (i.e., that Sweden did nothing). Sweden may have done well simply because they had a really aggressive and swift vaccine policy.

I don’t know enough about this, but I am somewhat skeptical of the way that many excess death calculations are estimated. Many don’t seem to account for changes in populations. Some are simple linear regressions of short term trends, like 3-5 years, sometimes adjusting for age composition and sometimes not. Almost none take account of demographic factors like migration and changing demographics. I’d love to see a paper that really pulls apart how these estimates are made. My quick reading of public health commentary on this suggests that there are initially unintuitive effects of things like immigration. For instance even though recent immigrants tend to be poorer on average, they tend to be healthier (otherwise they couldn’t migrate). Then there are replacement effects during pandemics—if vulnerable members of a population die early in a pandemic then expected deaths in future years should decrease because people who you may expect to die in year three from some “natural cause” die in year one due to an epidemic—so your expected deaths should be lower in year three than initial estimates suggest. But a linear estimate of pre-pandemic years is going to miss this. There will be a sort of natural mean reversion if you don’t account for the underlying change in the population as the epidemic evolves. So, there seem to be a host of factors that are not accounted for by a number of the excess death estimates that I have seen. Maybe these are all small magnitude effects that don’t really matter. But Sweden v. other Nordics in late 2021 and 2022 really puzzle me. In the end it may simply be that there was nothing we could do except delay the inevitable. The optimist in me hopes this isn’t true. But I’d love to understand this better.

Anyway, no real reason or action plan for sending this to you. Just wanted to throw out some unorganized thoughts that I had after reading your post a bit earlier today.

Best,

Troy

Troy has a Substack newsletter in case you’d like to subscribe.

One final thought. The focus on Sweden’s approach is understandable, since it was such an outlier and received a great deal of contempt and scorn at the time. But the data suggests that one ought also to look closely at the policies instituted in Norway and (especially) Denmark. On both economic and public health grounds Denmark appears to have done extremely well relative to its neighbors, though at the cost of some liberties that Swedes continued to enjoy.

Interesting article. I appreciate that you are looking at a highly charged subject with care and nuance.

Very interesting, the overly conservative behaviour in Sweden after experiencing the first wave may be mirrored by an excessive loosening in countries that experienced lockdowns and low mortality. This seems to me to characterise the dynamics in Australia, where precautionary behaviour largely disappeared once the lengthy lockdowns were lifted. People likely hah had enough of the constraints (with limited deaths) and were inclined to go back to a normal life.