While in New York on April 26th, I learned that my father was Covid-positive and in critical condition. His oxygen saturation had fallen to life-threatening levels and he was fading in and out of consciousness. When able to speak, he was delirious and incoherent. Others in the family, including my mother, sister, and brother-in-law were all symptomatic to varying degrees.

Through a combination of persistence, effort, and good fortune, my sister managed to get him admitted to a thousand-bed facility that had been set up by the military, where he was given enough oxygen and medication to make it through the night. I took a flight to Delhi on the 27th, arriving on the night of the 28th. My nephew met me at the airport, gave me a PPE suit and other protective gear, and drove me directly to the facility where he was being treated. No visitors were allowed but I managed to talk my way into entering as an attendant, based on a note that my sister had obtained from a doctor within.

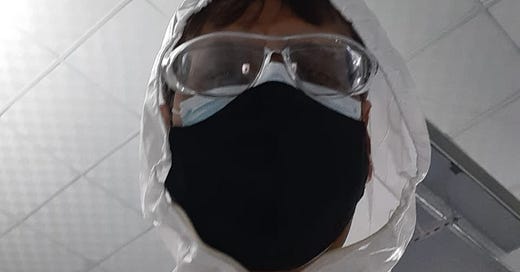

The experience of walking into a cavernous hangar with long lines of beds spaced a few feet apart, with all medical and housekeeping staff covered head to toe in white suits, gloves, masks, and face shields, is not one that I’ll easily forget. I found my father’s bed but since I must have looked largely indistinguishable from other staff he didn’t recognize me by appearance. He recognized the voice though, and I felt that my presence gave him some comfort. I stayed with him for a while then went home where my mother was waiting.

My mother has limited heart and lung function after having survived viral myocarditis over twenty years ago, but she is a nutritionist, a lifelong vegetarian, and active by nature. She relies on a pacemaker and nebulizer but otherwise appears quite healthy. For the past year we have been terrified of her getting Covid, thinking that she could not possibly survive it. But she surprised us all, handled eleven days of fever, stuck to her routine and medications, and got through it without fear or fuss.

The next day I returned to the makeshift hospital and found that my father had pulled his monitor down on his arm and head. It was no longer functioning. The staff was reluctant to replace it, thinking that he would just repeat the exercise and use up resources that others badly needed. I managed to calm him down and get the monitor replaced, helped him with a bit of food and drink, cleaned up around him, and stayed for a couple of hours.

The next day, April 30, I didn’t go back. I was told that I was putting myself at risk, the viral load in the facility was much too high, and that we just had to wait until discharge. And so we waited.

One day later, on May 1, my sister got a panicked call from my father, saying that we had to get him out of there, he couldn’t survive another night, had barely eaten or slept in three days, and was left unattended in soiled clothes and sheets. He wanted to die with dignity at home. But most people I spoke with thought it was folly to bring him back prematurely, he still needed oxygen around the clock and an IV drip. I decided to go back to the facility just to see if I could calm him down and get him to eat and drink a little.

When I arrived, he begged me to take him home. He tried to touch my feet, a sign of deep respect for one’s elders in India, and something unthinkable for a father to do for his son. He was in tears, close to a breakdown, convinced he could not last another night. My sister felt that I should just bring him home, while most others in the family thought he wouldn’t survive.

This was the hardest decision I’ve ever made in my life, and I hope to never face anything like it again. I didn’t know whether I’d be saving his life by bringing him home, or assisting a suicide.

The military doctor who was attending, a group captain whose name I can’t recall, agreed to discharge him against medical advice. I wheeled him out to the exit, where I was kept waiting for completion of paperwork. I saw him slumping in the chair, and feared that his oxygen saturation was falling fast. There was a trauma center near the exit where I managed to get him hooked up to an oxygen cylinder while discharge was completed. When saturation reached 94, I wheeled him to the car and began the drive home.

Driving in Delhi takes some adjustment for those accustomed to US cars, roads and rules. Transmission is manual, the steering wheel is on the right side of the vehicle, cars drive on the left (as in the UK), horns blare constantly, and there isn’t much attention to lanes in the road. Perhaps out of nervousness, I took a wrong turn and what should have been a fifteen-minute drive lengthened to twenty. By the time I got my father upstairs his oxygen saturation had fallen to 79.

We had a small amount of cylinder oxygen which we used to revive him, and a borrowed concentrator capable of generating five liters per minute indefinitely. Once he reached a tolerable level of saturation we switched him to the concentrator, which along with oral steroids has kept him alive since then. At first, I would check on him every hour or two through the night, making sure the tube was in place and that his readings were not falling. But he has recovered slowly, and no longer needs continuous care.

The most serious remaining concern is pulmonary embolism, caused by Covid. There is a clot in his lung, though thankfully not in the main artery. He has to take blood thinners but the initial dose caused gastrointestinal bleeding and had to be cut in half. This now appears to be working.

And that’s where things stand for now. One thing this episode has taught me is that time with loved ones is precious and not to be squandered.

I thought this tale was worth telling. Conditions in the country remain dire, much worse than is being reported in the media or can be seen in official statistics. Every day I hear of multiple deaths, which have included some distant relatives and others known to family and friends. Some of the people dying are very young. Most deaths could be prevented with wider availability of oxygen and controlled doses of steroids and antibiotics, and the inability to distribute these adequately has been an appalling failure of governance. But that’s a topic for another day.

send your father, you and your family lots of love and strength

Atlanta Frederick sisters sending you and your family love and our prayers.